Although the 1980s were not kind to most traditional monsters - vampires, mummies, gargoyles, and the like - however, the decade also offered a remarkably prominent werewolf movie. In the summer of 1981 John Landis' An American Werewolf in London was released. The very film which would, in many ways, set the standard for the modern werewolf movie. In the 34 years since its first release, it has not yet been surpassed (not even by the Jack Nicholson/ Mike Nichols collaboration, Wolf).

Often, there's an acute line between horror and humour. This evolves from the natural defence mechanism of the human psyche; laughing at something which causes discomfort. Hence, while some people are shocked and disturbed by a film like The Exorcist, others snigger and giggle like they're watching a cheesy Adam Sandler comedy. On rare occasions, directors attempt to exploit this fine link. Most of the time, they fail miserably, and the results can be painfully unfunny, parodic and non-frightening. However, a few filmmakers defy the odds and mine the right vein of ore. The list is disappointingly short, and includes names like Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead and its two sequels) and John Landis.

Landis came to An American Werewolf in London riding the crest of a wave of popularity. His two previous movies, Animal House and The Blues Brothers, had proven to be juggernaut box office successes. An American Werewolf in London would make it a trifecta. Afterwards, the director's career began a slow downward slide, beginning with the on-set disaster associated with his segment of The Twilight Zone. Landis rebounded briefly with Trading Places, but, by the roll around of the '90s, he was mostly regarded as a has-been and living proof of how easily even a proven filmmaker can fall out of favour in the industry.

In terms of storyline and plot structure, there's nothing innovative and unforeseen about An American Werewolf in London. What makes this film unique is its successful marriage of horror and comedy. The humorous sequences are funny enough to laugh at, while the gruesome scenes retain the power to fright. This ability to refrain from being a mimicry, is in large part due to the identification of the main character, whom we hope against odds will find some way out of the story’s impossible predicament. Had this individual been imbued with less humanity, he would have turned into a caricature and the entire film would have devolved into a grotesque farce.

The movie opens in the wild moors of Yorkshire, where two Americans, David Kessler (David Naughton) and Jack Goodman (Griffin Dunne), are on a backpacking trip. By the time they reach a small village near the threat of nightfall, they are freezing and famished, so they decide to stop in at the local pub, a place with the ominous name "The Slaughtered Lamb". Their reception there is decidedly frosty, as they receive angry glares from the customers and the barmaid. After they ask one too many questions, they are rudely told to leave, although, before departing, they are given a warning to stick to the road and not wander onto the moors - a warning they ignore, much to their regret.

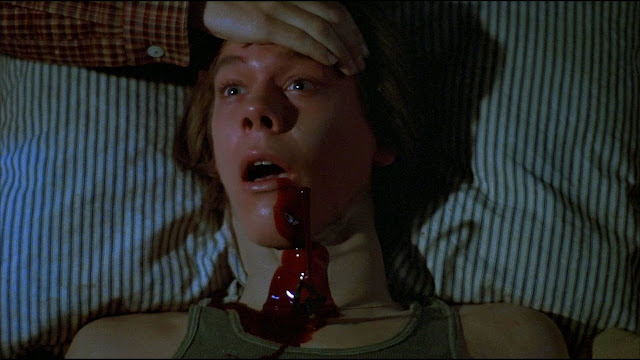

When it comes, the attack is swift and merciless. A huge, wolf-like creatures leaps from the shadows, savagely killing Jack and injuring David before several of the townspeople, armed with guns, subdue it. The next thing David knows, he is recovering in a London hospital under the tender ministrations of a captivating nurse named Alex Price (Jenny Agutter) and the pragmatic Dr. Hirsch (John Woodvine). Despite a series of harrowing nightmares, David seems to be progressing - until he receives an unsettling visit from his zombified friend, Jack, who informs him that he has become one of the walking dead and that David, on the night of the next full moon, will exhibit the curse of lycanthropy and transform into a werewolf.

Of the three early-'80s werewolf movies, the transformation sequences in An American Werewolf in London are the most effective, beating out those in The Howling by a slobbering snout (Wolfen isn't even up to par enough in the running). There are a lot of similarities, which should come as no surprise, since both were supervised by makeup man extraordinary Rick Baker (who was also responsible for changing Jack Nicholson from man to beast in Wolf). Baker, working with "old-fashioned" tools like prosthetics and makeup, creates a series of memorable and lasting images. The transformation starts with David leaping up from reading a book after an extended sequence of pacing and worrying in anticipation of the full moon., “Jesus Christ! Jesus Christ! What?” is all we hear… just before he tears at his clothing, perspiring and mewling out of pain, limbs begin to elongate, mangle, and sprout tufts of hair. David writhes on the floor and we hear what sounds like cracking bone. It’s a far cry from the fade-in transformation of Lon Chaney Jr. in 1941’s The Wolfman (a film that gets name-checked and referenced throughout American Werewolf). This transformation looks excruciating. It’s also held up considerably well in the more than thirty years since the film’s initial release. All in all, it is no surprise that Baker claimed an oscar for his work in the department.

In the end, An American Werewolf in London successfully attempts to update the werewolf genre; there is no such thing as silver bullets or other silly plot points unlike prior werewolf movies. This horror classic attempts to simplify the lore and the fact that it is humorous does not hinder the sinister elements, or the impact of the creature. Because what does the werewolf lore represent? It represents the idea of stripping someone of their humanity and leaving them at their most primal state. The werewolf-phobia or ‘lupophobia’ seems to stem from the fear of humanity at its most basic form. This is quite possibly why the darker tones of An American Werewolf in London mix perfectly with the abundance of absurdity, as the link between humanity and overwhelmingness of animalistic instinct is present and presented, excellently throughout the film. Without a doubt, it's my favourite werewolf flick proves to be just one of those movies that you’ll never really be through with, a classic.